Moving to Commercial Construction - eBook (PDF)

Commercial construction work is usually larger than residential, the payoff is better and you don't have to deal with homeowners. But commercial jobs have risks of their own, and if you are not careful you can lose your shirt.

If you've been thinking of taking on more commercial jobs, you should have the information in this new book. It offers the general contractor, subcontractor, and designer some step-by-step methods to making the move from residential to commercial construction a successful one.

Covers finding commercial work, compiling and estimate and presenting a bid, getting through the submittal and shop drawing process, working with owners, architects and subs, and controlling your costs and insuring profit.

This e-Book is the download version of the book in text searchable, PDF format. Craftsman eBooks are for use in the freely distributed Adobe Reader and are compatible with Reader 5.0 or above. Get Adobe Reader.

Free construction forms and contracts from this book you can download and use.

Commercial construction work is usually larger than residential, the payoff is better and you don't have to deal with homeowners. But commercial jobs have risks of their own, and if you are not careful you can lose your shirt.

If you've been thinking of taking on more commercial jobs, you should have the information in this new book. It offers the general contractor, subcontractor, and designer some step-by-step methods to making the move from residential to commercial construction a successful one.

Covers finding commercial work, compiling and estimate and presenting a bid, getting through the submittal and shop drawing process, working with owners, architects and subs, and controlling your costs and insuring profit.

This e-Book is the download version of the book in text searchable, PDF format. Craftsman eBooks are for use in the freely distributed Adobe Reader and are compatible with Reader 5.0 or above. Get Adobe Reader.

Free construction forms and contracts from this book you can download and use.

| Weight | 0.000000 |

|---|---|

| ISBN | 1-57218-103-6 |

| Page Count | 256 |

| Author | Stephen S. Saucerman |

| Publisher | Craftsman Book Company |

1

The Change, 5

Don’t Worry, You’re Not Alone, 5

The Construction Industry, 7

2

Staffing the Commercial Construction Office, 13

Weighing

Your Needs, 13

Staffing Your Office, 15

Independent Contractor vs. Employee, 22

The Office Itself, 23

3

Finding Commercial Work, 29

Covering

Office Overhead, 29

Residential Bid Opportunities, 29

Commercial Bid Solicitation, 30

4

Working With Architects and Engineers, 37

The

Architect, 37

The Engineer, 42

Professional Organizations, 43

5

Construction General Requirements, 45

Why

Should You Care About General Requirements? 45

Administrative General Requirements, 47

Field General Requirements, 51

6

Creating a Winning Estimate, 55

Commercial

Construction Estimating, 55

The Estimating Process, 56

Conclusion, 83

7

Owner/Contractor Relationships, 85

Types

of Commercial Contractor/Owner Relationships, 85

Fee Arrangements, 87

The Problem with Competitive Bids, 94

The Competitive Difference, 96

If Not Competitive Bid - What Then? 97

8

Design/Build and Partnering, 99

What

Is Design/Build? 99

The Pros and Cons of Design/Build, 100

Partnering, 103

Conclusion, 106

9 The

Submittal and Shop Drawing Process, 107

The

Process, 107

Why Have a Review Process? 112

Final Thoughts, 113

10

Subcontractor and Supplier Selection, 115

The Selection Process, 115

Purchase Orders and Subcontractor Agreements, 121

The “Buy-Out”, 122

11 The

Profitable Job Site, 127

Making or Losing Money in the Field, 127

Construction Delays, 130

The Change Order Challenge, 141

Conclusion, 148

12

Employee Turnover and Morale, 149

Investing in Your Employees, 149

Taming the Beast, 153

A Course of Action, 156

Conclusion, 157

13

Project Closeout and Warranty, 161

The Job That Wouldn’t Die, 161

Project Closeout Requirements, 162

Don’t Wait Until the End, 169

14

Accounting, Collections, and Your Financial Health, 175

The Importance of Accounting, 175

Bookkeeping vs. Accounting, 175

Common Bookkeeping Duties, 176

Cash Flow, 183

Collection Procedures and Overdue Accounts, 184

Computers, 187

15

Bonding, Insurance, Workers’ Compensation and Safety, 189

Business Failures, 190

Bonding Companies, 190

Insurance, 193

Safety and Workers’ Compensation Insurance, 194

Other Insurance Needs, 201

16

Marketing and Promotion, 203

Marketing Tools, 203

Customer Presentations, 210

Trade Shows, 212

Other Ways to Get the Word Out, 213

Getting the Advertising Juices Flowing, 214

17 The

ADA Impact, 215

The Americans With Disabilities Act, 215

Common ADA Applications, 217

The Consequences for Noncompliance, 220

Resource Information, 222

18 The

Contractor, the Computer and the Internet, 223

Computer Basics, 223

The Computer and Commercial Construction, 224

The Internet, 231

19

Success and Failure in Commercial Construction, 237

Ten Dumb Things We Do to Spoil Our Own Success, 237

What’s on the CD, 243 (CD not available with eBook)

Index, 245

Chapter One - The Change

Owners and managers of residential contracting businesses make scores of crucial decisions every day that affect the future of their companies — but none are so potentially risky as whether or not to expand their residential operations into commercial ventures. Commercial contracting (and the commercial building process) often seems to be an intimidating departure from the residential contractor’s customary routine. And rightly so.

Taking this step involves considerable change. Suddenly, new and unfamiliar responsibilities become part of the contractor’s daily building activity. Words and phrases such as liquidated damages, bid bonds, contingencies, and prevailing wages find their way into the conversation. Acronyms like OSHA, HAZCOM, CSI, ANSI and ASTM pepper the rather bulky commercial project specification manual (also new to the former residential contractor). They make it read more like a foreign-language code book than a building guide.

All in all, it can be an overwhelming plunge into a new area of expertise that’s not quickly or easily grasped. But you’ve made up your mind: It’s time to expand, and commercial contracting is the direction you feel you must take. So where do you begin?

Don’t Worry, You’re Not Alone

The anxiety you’re feeling is natural, and completely justified. Commercial construction is a different world, presenting fresh challenges, new and more stringent procedures, and (if all goes well) greater rewards. But, like most good things in life, success in commercial contracting comes at a cost. Fortunately, that cost will decrease as your knowledge and experience in commercial construction increase. In short, if you’re going to get into the game, you’re going to have to learn the rules and you’ll probably also have to pay some dues!

I can relate to what you’re going through. Before I ventured into commercial contracting, I spent many years in residential construction. I enjoyed the challenge that residential work offered and found the results rewarding, but there came a time when the routine (mostly new housing) became boring. I could feel myself growing stale.

At the same time, new competition was springing up every day and my profit margin seemed to be dropping rapidly. I was ready for a change, and commercial construction seemed the ideal route to take. It offered the opportunity for building on a grand scale, taking on an elevated occupational status, and, I was sure, an equally elevated income. Never mind whether this vision was real or not — that was how I pictured reality at the time. So I decided to make the jump, and I haven’t looked back since.

Making the Jump

But it wasn’t an easy transition. There was a lot to learn in a very short time. I was suddenly at the bottom of the experience food chain, struggling to climb up. Clearly, I needed to do some quick research into this new profession, but what I discovered was the first of the many surprises I would encounter in commercial construction.

You see, when I went searching for information to guide me into the business of commercial construction, there was very little to be found. Sure, the library had scores of books on construction itself, but few of these offered assistance with the business end of any field of construction — and virtually none offered that information on commercial construction. In fact, what little information I did find was more often than not:

-

Thirty years old and sorely outdated

-

Handyman and/or home improvement guides (“Changing the washer in your faucet” or “Building a backyard barbecue”)

-

How-to books for carpentry, framing, masonry work and so on

-

Long-haired, scholarly construction-management guides written by people who clearly hadn’t had much, if any, experience with a hammer

There seemed to be a missing link in the learning-how- to-do-it equation — and that’s the gap I hope to fill for you.

What This Book Is About

This is a complete commercial-construction business reference, geared specifically to the average residential building contractor looking for a change. It offers today’s residential general contractor, sub-contractor, material supplier and designer a practical guide to making the complex transition from residential to commercial construction.

In the following chapters you’ll find the real-life, common-sense guidance that I wish I had found when I made my switch. I had to learn the hard way, and I’ve made the mistakes — so you won’t have to. I’ve also developed some creative and positive techniques that helped me make this transition manage-able, profitable, and occasionally even fun. You’ll find those here, too.

What This Book Is Not About

This is not a book about construction management. We will not dissect structural details, nor will I tell you how to make the picture-perfect concrete pour. Neither will we create seemingly-endless PERT charts, and (I promise!) you won’t see the phrase “activity-on-node” even once.

I realize that construction management topics are interesting for builders, but there are already many excellent references available on these subjects. (You’ll find a list from Craftsman Book Company in the back of this book.) And besides, they simply aren’t relevant to our goal for this book. Instead of teaching you how to build, we’re going to teach you how to move your current residential operation into commercial markets with as little disruption of your business, and your profits, as possible. We’ll focus on the transition itself; how your goals will be altered, how your life will be changed, and how your horizons will be expanded.

But enough talk . . . it’s time to get started. So, kick off your work boots, and get ready to make that move!

But First, a Few Ground Rules

I’ve made one important assumption while writing this book. I’ve assumed that you are (or were) involved in the residential construction or remodeling field and you have a fundamental knowledge and understanding of construction in general. This was necessary to avoid making the discussion too basic.

Also, I’ve opted to use “he” and “his” over “he/she” and “his/hers” in places where it’s relevant. This is simply for the ease of reading, and definitely not meant as a slight to my female associates who make up a large and critical portion of the construction industry. And who, with the advent of thriving organizations such as the National Association of Women in Construction, will only continue to grow as an influence.

Finally, I’ve had to decide on a representative size (expressed in dollar volume of sales) for the commercial contracting company to target in this book.

This was necessary because running and analyzing a $5-million commercial construction company is significantly different from one doing $200 million or more, particularly when it comes to staffing, types of work, and administration. So I’ve chosen to base most of our discussion and examples on a commercial contracting firm that does approximately $5 to $20 million in annual sales.

I picked this particular level for two reasons. First, it’s the dollar volume that I’ve worked with over the years, so it’s by far the most familiar to me. Secondly, and perhaps most important, this is the dollar volume that I believe most of you will eventually fall into. You probably won’t start off that high, more like $2 million in the beginning, but after a few years your company should be approaching the $5 to $10 million range. That’s a realistic goal. I know far more commercial construction firms in the $10 million per year sales bracket than in the $200 million per year bracket. And, quite frankly, if you’re doing (or have the ability to do) $200 million per year, you should be writing this book — not reading it!

The Construction Industry

As technology advances and populations grow, the need for quality commercial construction grows accordingly. New businesses will be created, new manufacturing facilities will be built, and existing firms will expand, renovate, or rebuild operations to meet the ever-developing world demand. The work is out there. All you have to do is go after it.

Residential Contracting

Before we make that leap, let’s define our players. We’ll start with where you are now. As the name implies, residential contractors are those professionals who involve themselves primarily in aspects of residential building and remodeling — most often working with single-family homes. This group includes a variety of professional trades that are very similar to those in commercial construction, including general contractors (GCs), subcontractors, building material suppliers, and more.

Although the residential GC is the overall leader of the project, he must work with subcontractors, whose trades break down into subgroups of skilled and semi-skilled-workers. These subcontracted trades include plumbers, electricians, painters, carpenters, carpet layers, plasterers, excavators, and so on. All of the trades and material suppliers come together to form the team of residential construction professionals who create and maintain the homes and apartments in which we live.

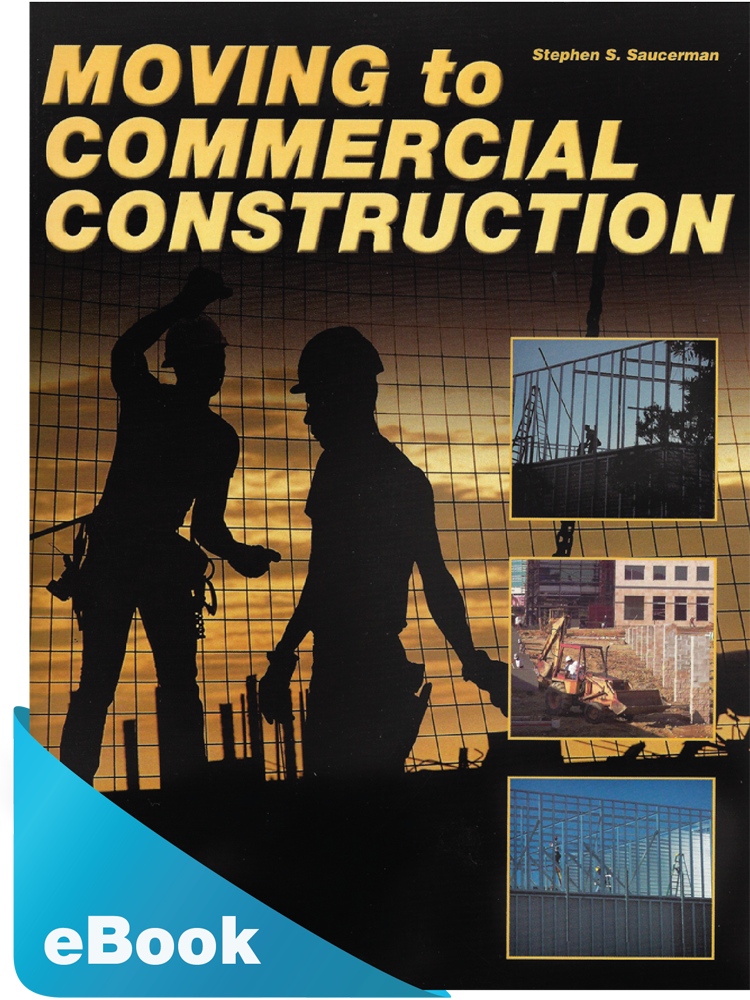

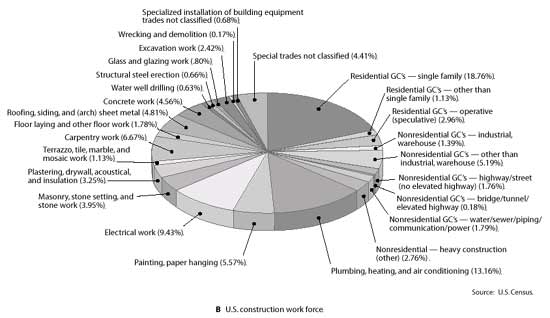

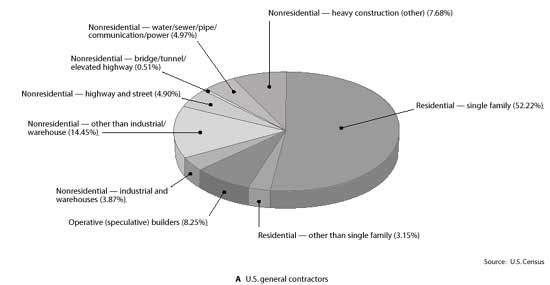

Figure 1-1 Construction Breakdown by Trade

(A) U.S. General Contractors

Taken as a whole, the number of persons employed in residential construction is staggering. According to a recent U.S. Census, there are over 100,000 residential general contractors, who employ over 500,000 workers. Including single-family, multifamily and speculative contractors, they account for approximately 64 percent of the total general contracting market (Figure 1-1 A). On top of this there are legions of people working in residential subcontracting fields (shown in Figure 1-1 B), material supply, design, regulatory agencies, and related administrative fields.

Figure 1-1 Construction Breakdown by Trade

(B) U.S. Construction Work Force

This makes residential construction one of the largest employers in the U.S., if not the world. With so many participants, and so much power behind them, it’s no wonder that they enjoy an abundant supply of information, assistance, and networking resources. There are residential builder’s organizations, home design and construction publications, and even home-building and repair shows on public television. So why, if residential contracting has so much going for it, would anyone want to leave the fold?

The Bad News for Residential Contractors

Well, as it happens, this same abundance of participation in the field also creates an overabundance of competition and market pressure. There were times when I felt everybody I knew was a home builder or remodeler. Competition came out of nowhere. It often seemed that I belonged to a group where it was simply too easy to become a member.

In fact, in my market area, we had a far-too-frequently reoccurring phenomenon. Whenever the workers in our local auto plant (the primary employer in our town) went on strike or suffered layoffs, a disproportionately large number of new residential builders would suddenly appear on the scene. They had names like B & D, S & S or B & J — always follow by the term Builders. Those of us who were in the business for the long run assumed that the two initials belonged to two former auto workers who decided to join forces and become builders following the latest layoff.

Few were licensed (often, it wasn’t required), and many were totally inexperienced. Yet, there they were. Of course, many of them merely flickered and then died away, but not before they managed to inflict a considerable amount of damage on those of us remaining in the local industry.

They would bid a half-dozen jobs at a cost well below their established competitors. Their clients — who thought they were getting a great bargain — greedily accepted the low bid with little or no investigation into the builders’ background. You can probably guess the rest. Their projects inevitably floundered, the work was of poor quality or went uncompleted, another company had to be called in to finish the work, and B & D Builders was gone.

But the damage to the local market had already occurred. They had created expectations for an artificially low price among homeowners and home-buyers. A few of the established companies would try to match the prevailing rates and increase their volume to make up for their decreased profit margins — and that would further dip into our pool of prospects.

Desperate for sales, we’d find that we not only couldn’t increase our profit margins, but we were actually having to decrease our markup just to keep up with the pack. It doesn’t take long until your profits are no longer covering your overhead, and you’re on the verge of following B & D Builders into oblivion. Some of the companies survived this scenario, but many didn’t. If you’ve been in this business long, you’ve probably seen this happen more than once.

Moving a Little Closer . . .

So you look to commercial construction. You see less competition in commercial work, and (most of the time) greater dollar volumes. Assuming that the profit percentages between residential and commercial are similar, a little quick math leads you to the rationale that “as long as you’re going to expend the energy, why not take your profit percentage out of, say, $2,000,000 rather than $150,000?” And with fewer competitors, you think that you just might be able to find a niche (a singular market segment) that will satisfy your financial and business needs. With this in your mind, you find yourself one step closer to making your move.

Commercial Contracting

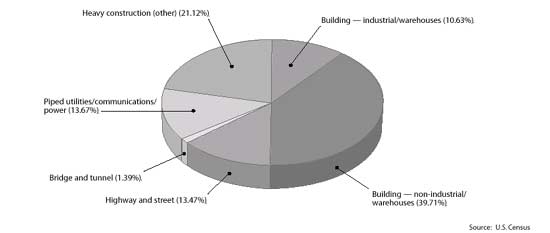

Commercial contracting is generally described as the construction of any project of a nonresidential nature — which is a pretty broad definition. It basically excludes single-family homes and rental properties up to about four units (depending on who you’re talking to). It includes an almost limitless number of categories such as institutional, medical, manufacturing, civil, and so on. Figure 1-2 shows some of the common commercial construction categories.

Figure 1-2 Work Specialty for Commercial

Contractors

Commercial General Contracting vs. Construction Management

One of the first decisions you’ll need to make about commercial contracting will be your overall business philosophy. You need to decide on what approach to take in your new market. Do you want to be a:

-

commercial general contractor (CGC),or

-

construction management company (CM)?

Although there are specialized situations in commercial work where a subcontractor is the lead or prime contractor (which we’ll discuss later), a CGC or CM is generally hired to head up commercial construction projects. The differences between these two can seem a bit murky at times, so let’s take a closer look at them.

Commercial General Contracting — A commercial general contracting firm is the more familiar type. They’re often family-owned and run, some-times two or three generations deep. They may employ three to seven full-time staff or family members in the office, as well as a few full-time trades-men. The tradesmen are often carpenters who double as job superintendents, but they could also be cement masons, bricklayers, or excavators, depending on the CGC’s specialty. The company may also keep additional trade employees on staff to make up crews for work that the firm does “in-house” (work that they don’t subcontract out).

This group of full-time employees (those enjoying employee benefits, such as insurance, retirement, vacation, etc.) forms the nucleus of the organization. The rest of that contractor’s work is completed with the help of subcontractors, suppliers, temporary workers, and other outside independent contracting firms (those providing their own benefits).

The number and type of key personnel is one notable difference between the CGC and the CM. Another difference is how they obtain their work. Although many older and more established CGC’s enjoy a good percentage of negotiated work, most of their work comes from the competitive bid process. This is especially true of newer firms that haven’t achieved the name recognition or clientele of an older, family-owned business.

We examine both the negotiated and competitive bid processes in depth later on in the book. For now, here’s a brief look at the competitive-bid process.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Construction

Management — In

a construction management situation, the construction manager (CM)

approaches the business a bit differently: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Drawing Conclusions

In short, the difference between the Construction General Contractor and Construction Manager is more about the managerial arrangement and the relationship between the owner and the contractor, and less about the actual techniques of building the construction project itself. The same mason or electrician will more than likely be working on the job regardless of whether the lead player is a Construction General Contractor or a Construction Manager.

This comparison should give you some help in making your decision on how you want to define your new role in the commercial market. Of course, you won’t be able to just grab onto this idea and use it. It’s more likely to be a gradual decision, molded over time by your own experiences

While the business of residential construction is rewarding and can yield a good living, it’s very competitive and highly dependent on local economic conditions. You often have to take any new job you can find just to stay in business, and deal with nagging homeowners, while watching your profit go down the drain. Sometimes the effort isn’t worth the money.

That’s why the author of this book turned to commercial work. A single job can keep you and your crews busy for a year or more. Though there is higher risk involved in commercial construction, there are greater challenges and higher profit as well. And, as long as you are going to expend the energy, why not take your profit percentage out of $2,000,000 rather than $200,000? But there’s a lot to learn, and plenty of room for mistakes. But as you’ll be shown here, there are guidelines to follow to help ensure your success.

If you’re considering making the jump from residential to commercial contracting, this is the book you need. It offers the residential general contractor, subcontractor, material supplier and designer a practical guide to making this complicated but rewarding move. In simple language, it explains practically everything you need to know, providing detailed guidelines for:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moving to Commercial Construction is a complete commercial construction business reference. It takes you step-by-step through the process of setting up a successful commercial company, with special emphasis on the intricacies of commercial estimating and bidding, value engineering, maintaining a profitable jobsite, keeping a stable work force, developing and maintaining successful business relationships, and promoting your business. There’s also a chapter on the design/build and partnering business concepts and their advantage over the competitive bid process.

| (SOFTWARE NOT AVAILABLE WITH eBook PURCHASE) |

The Author

Stephan S. Saucerman is a commercial construction estimator and project manager for Gilbank Construction, Inc. in Wisconsin, where he estimates and manages projects that have ranged from hospitals and office buildings to $8,000,000 multiple-unit housing tracts and commercial interior renovations as high as $9,000,000. He also teaches building construction technology part-time, at Rock Valley College in Rockford, Illinois, and is a regular writer/contributor for over 40 building industry publications in the U.S. and around the world. His career in the construction industry started a quarter century ago in building material sales, then onto architectural drafting, residential home building, and finally the move to commercial construction. He is a frequent speaker at seminars, building-industry conventions, and expos on a variety of construction-related topics